Should the United States as a constitutional republic soon collapse, the specific cause will be the failure to prosecute the act of sedition performed by Donald Trump on January 6, 2021. A corrupt political culture and an ineffective justice department have led to this crisis. Carol Leonnig and Aaron C. Davis, reporters for The Washington Post, have offered an in-depth analysis highlighting failings within the Justice Department. This powerful and disturbing book, “Injustice: How Politics and Fear Vanquished America’s Justice Department,” reads like a coroner’s report on our democracy.

This is an essential read that details the most important event in U.S. History since the Civil War. It will be very difficult to explain to future generations how President Trump managed to avoid consequences for January 6. It is a complex and dense story but one made accessible to a broad audience by the capable work of Leonnig and Davis. Collectively, they have earned seven Pulitzer Prizes—five awarded to Leonnig and two to Davis. Notably, one of Davis’s Pulitzers specifically recognized his coverage of January 6, for which he also received the George Polk Award and the Toner Prize.

The authors describe their book as “a tragedy in three acts.” (xix). Act One took place during President Trump’s first term, when he directed Justice Department officials to advance his personal interests rather than upholding the independence of the Department and the primacy of the Constitution. Act Two examines the Justice Department’s response under Biden to the January 6 events, the attempts to overturn the election, and Trump’s handling of classified documents at Mar-A-Lago. The Final Act examines Jack Smith’s actions, the Supreme Court justices’ interference in his investigation, and the Justice Department’s shift toward protecting Trump and targeting his opponents after his reelection in 2024.

RUSSIA RUSSIA RUSSIA!

When President Trump began his first term in 2017, there was considerable evidence indicating connections between certain members of his campaign and individuals with associations to the Russian leader Vladimir Putin. The FBI began investigating Trump’s Russia ties in 2016 under James Comey. Trump fired Comey on May 9, 2017, after Comey declined to publicly state that Trump was not under investigation. One week later, Deputy Attorney General Rob Rosenstein appointed Robert Mueller as Special Counsel to continue investigating Russian interference in the 2016 election. Rosenstein made this appointment because Attorney General Jeff Sessions had recused himself from the case due to his own connections with Russia. The Mueller Report was finished shortly before Trump’s July 25, 2019 “perfect” call to Volodymyr Zelensky, which led to his first impeachment trial.

Attorney General William Barr misrepresented the Mueller report’s findings, frustrating most attorneys who worked on it for two years. Barr inaccurately stated there was no obstruction. There was substantial evidence suggesting obstruction by Trump and his associates, but Mueller chose not to indict a sitting president or make evidence public without allowing the president to respond. Essentially, the evidence for obstruction was strong, which raised concerns about why DOJ prosecutors did not push harder to pursue the obstruction case. Had there been an obstruction trial, it might have uncovered further details about collusion, potentially resulting in multiple indictments.

Many DOJ prosecutors were further frustrated that Mueller refused to have Trump testify under oath, which would have required Trump to formally acknowledge or deny the strong evidence of connections between Putin’s operatives and his own advisers and family members. There is precedent for presidents having to testify as defendants in cases that took place while they were in office or at least to submit subpoenaed material.

Barr’s misrepresentation of the attorneys’ findings on Russian interference has cast unwarranted doubt on the Mueller report and further fueled claims of deep-state opposition to Trump. Barr’s inaccurate characterization has led to a reduced public

understanding of the extent of Russian involvement in the 2016 election, as well as Russian activities in U.S. elections more broadly. An illustration of the careful approach taken during the process is that investigators decided against including evidence indicating that a Russian oligarch may have financed a troll farm which regarded itself as instrumental in Donald Trump’s 2016 election. On election day in 2016, these Russian trolls raised their champagne glasses and proclaimed: “We made America great.” Putin’s Duma did the same.

Leonnig and Adams provide insight into the reasons behind Mueller’s limited public presence since the publication of his report in April 2019. Mueller has since retired to an assisted living facility, where he is experiencing cognitive decline and symptoms consistent with Parkinson’s disease. Some of the cognitive symptoms were already apparent in the waning weeks of the investigation associated with his name. This may also be why the Attorney General has not indicted him, like it has done to others involved in investigating Trump’s criminal activities.

After Barr had torpedoed the Russia investigation, he slyly proceeded to weaken the case involving a similar interference in the US election by Egypt. This story emerged during Mueller’s Russia investigation. Five days before Trump’s inauguration, four people—including two Egyptian intelligence agents—left the Bank of Egypt with bags containing $100 bills totaling $10 million. (Interesting detail: $10 million in bags of Benjamins weighs about 220 pounds, the same weight that Franklin carried in his later years!) While the Egyptian interference case was strong, it needed supporting evidence from Trump’s bank records. The U.S. Attorney expressed reluctance to subpoena those records without the approval of Attorney General Barr. Barr referred the decision to the FBI, which likewise demonstrated hesitation to pursue presidential bank records without explicit authorization from the Attorney General. It was a circular passing of the buck.

A host of circumstances thus denied the Mueller Egypt team access to the records they need to pursue their investigation. Trump had threatened to fire Mueller should he investigate Trump’s finances. Out of respect for the assumed privileges of the presidency, Mueller acted with extra caution and permitted his team to subpoena Trump’s Capital One bank records only for the period before the November 2016 election. The Bank of Egypt claimed immunity as a sovereign government agency and refused to provide subpoenaed records, a stance that surprised the chief judge of the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C. Although DOJ prosecutors had the option to obtain Bank of Egypt records, Barr made moves that hindered the investigation into secret financial backing from Egypt for the Trump campaign. He replaced Jessie Liu, the lead U.S. Attorney, with Trump loyalist Tim Shea, who then closed the Egypt investigation. As a result, information about foreign interference from Russia and Egypt was withheld from the public. It gets worse.

Andy McCabe & Mike Flynn

Barr’s impact was especially clear in the Department of Justice’s case against Andy McCabe, the FBI Deputy Director. Both McCabe and Michael Flynn were accused of lying to federal agents about minor issues, but Barr pursued the charges against McCabe vigorously while discouraging action against Flynn. The main distinction between the two was that Flynn supported Trump, while McCabe had criticized him.

Before McCabe was charged, officials in the Trump administration pressured FBI director Christopher Wray to dismiss McCabe. Wray resisted until January 2018, when an Inspector General’s report claimed McCabe lied to federal agents. At that point, Wray urged McCabe to resign, but McCabe believed the case was politically motivated and legally weak, so he refused. When McCabe would not leave on his own, Attorney General Jeff Sessions fired McCabe on March 17, 2018, just days before his scheduled retirement. When Barr became AG after Sessions resigned on November 7, 2018, he continued with the case against McCabe and brought it before a grand jury. Eighteen months later, the grand jury declined to indict McCabe. He was vindicated.

While McCabe was accused of misleading the FBI regarding his communication with the Washington Post about the Clinton Foundation, Michael Flynn was accused of making false statements concerning his interactions with a Russian ambassador.

Leaking information to the press or holding discussions with a foreign diplomat are not themselves criminal acts; however, providing false information to the FBI constitutes a crime. A grand jury declined to charge McCabe, while Flynn pleaded guilty under a plea deal on December 1, 2017.

Flynn faced more serious and complicated charges than McCabe. Flynn had not only lied about his conversations with Russia, he also had failed to declare that he had received $500,000 in compensation from the government of Turkey prior to his taking a role as Trump’s National Security Advisor. When Flynn received his plea deal upon admitting guilt for lying about his ties with Russia, he did so with the understanding that he would provide testimony against the Turkish business partner that had paid him to be a special liaison to the Trump administration.

Barr proceeded to fundamentally weaken the case against Flynn. He promoted the inane notion that the entire case against Flynn had not been properly predicated. That is to say that the DOJ had no reason to investigate Flynn in the first case even though Flynn had confessed to breaking the law by lying to FBI agents in 2017. The FBI knew Flynn lied because Russian Ambassador Kislyak’s phone had been tapped during the conversation they had had. Two career prosecutors resigned instead of signing a statement admitting flaws in the case, while nearly two thousand former DOJ employees publicly called for Barr’s resignation, citing his undermining of the rule of law.

Barr intentionally complicated Flynn’s case so much that, by summer 2019, Flynn withdrew his plea agreement, effectively undermining the prosecution of the Turkish company. At that point, the government could have revoked Flynn’s plea deal and put him on trial. Barr, however, worked to ensure that did not happen.

Since the release of Injustice, Michael Flynn has filed a $50 million lawsuit against the federal government, claiming he was prosecuted for political reasons by the FBI and special counsel Robert Mueller. In his lawsuit, Flynn asserts that he was targeted as a “direct threat” to the so-called “deep state.” No one will be surprised if Bondi’s DOJ settles with Flynn out of court using taxpayer funds.

The Roger Stone Sentencing

While the Flynn case was unfolding, Barr also employed the DOJ to grant legal favors to Roger Stone. Stone had committed serious offenses for which a federal jury found him guilty on seven felony counts including making false statements to Congress on five occasions, obstructing a congressional investigation, and witness tampering. Additionally, Stone posted an image on social media showing the presiding judge with a crosshair near her face. Prosecutors rely on sentencing guidelines to recommend penalties for such crimes, and in Stone’s case, these guidelines suggested nine years of imprisonment.

That, however, is not how Barr saw justice for this Trump ally. Barr attempted to remove references to threats of violence and intimidation from the witness tampering charges to encourage the judge to lower the sentence. He convinced the attorneys to omit these details from their written recommendation, though they were permitted to mention them during oral testimony. In the end, Barr was able to circumvent the attorneys and revealed to FOX News sources his intention to reduce the sentencing recommendation. This prompted all four principal prosecutors assigned to Stone’s case to resign.

Bill Barr is a contemptible human being, but there was a line that even he would not cross. Already in 2020, Trump had wanted to replace FBI Director Christopher Wray with the utterly unqualified Kash Patel, who had previously served as an aide to Devin Nunes. Barr was willing to oversee travesties of justice, but he seemed unwilling to let it devolve into blatant farce.

The Voter Fraud Fraud

Alongside impeding investigations into possible foreign interference in President Trump’s election, Barr also helped lay the foundation for the “Big Lie” claims about widespread voter fraud. These claims were based on worries that mail-in ballots could make it easier for different types of fraud to occur. In September 2020, nine military mail-in ballots were mistakenly discarded in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania. The FBI investigated, determined a janitor with cognitive disabilities was responsible, and recovered all the ballots. The issue was properly resolved in accordance with DOJ guidelines. That, however, was not sufficient for Barr.

Barr made the incident public, presenting it as part of an ongoing investigation that supported Trump campaign claims about the 2020 election being rigged. His deputy even considered sending troops to locations where votes were being counted. These actions eroded confidence in the election’s integrity, fueled the spread of the “Big Lie,” and paved the way for attempts to overturn the 2020 election and disrupt the peaceful transfer of power.

Barr did not anticipate the events of January 6, perhaps the biggest failure of all in his dismal tenure as Attorney General. He and the FBI repeatedly failed to respond to warnings about groups like the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys planning an armed attack on the Capitol. The FBI also had evidence that some top advisers to Trump were involved in preparations for that day.

Despite all the corrupt things Barr had done to protect Trump and his allies, he was unwilling to participate in overturning the results of the 2020 election. On December 1, Barr publicly stated there was no evidence of voter fraud that could change the election results. That same day, Trump forced Barr’s resignation. Trump continued to coerce Barr’s successor, Jeffrey Rosen, who had been the deputy attorney general before becoming acting attorney general. Trump pleaded with Rosen to merely cast doubt on the election “and leave the rest to me and the [Republican] congressmen.” [90] Trump had anticipated Rosen’s resistance to this plan and had already discussed placing the more compliant and unqualified Jeffrey Clark as AG. That scheme, however, did not work.

When Clark was unable to persuade Rosen and other senior Justice Department officials to advocate for an appeal to the state of Georgia regarding its election results, former President Trump sought to dismiss Rosen and appoint Clark in his place. However, confronted with the prospect of widespread resignations among senior Justice Department officials, Trump decided against that course of action. These events transpired during the 72 hours preceding the January 6 assault on the Capitol, an event that the FBI woefully misunderstood. As Leonnig and Davis conclude about J6: “The Justice Department could only respond to the events of January 6 with the same hesitation and diffidence with which it had prepared for them.” [116]

That is far too kind. They failed to grasp the violent and destructive core of the ideology behind the MAGA movement. That misunderstanding continued under the Biden administration’s DOJ.

************

Garland Starts Slow, then Tapers off…

President Biden’s choice to nominate the moderate Merrick Garland as Attorney General was made before the MAGA-inspired violent act of sedition occurred on January 6. After January 6th, it seemed possible that moderate Congressional Republicans were sufficiently dissatisfied with Trump that they might do something to uphold the integrity of the constitution. Garland served as a strong example of an individual dedicated to maintaining impartiality in the judicial system. Biden saw Garland as the best choice to restore faith in the republic. Biden, moreover, needed Republican backing for key judicial appointments, and moderate Republicans would likely be willing to accept Garland.

But here we need to consider not just the depth of destructiveness of the Republican Party in general, but the utter incapacity of the U.S. Senate to act with integrity. Garland’s confirmation passed with a 70-30 vote. This means 30% of Senators chose not to support this consistently fair and moderate judge for the position. In fact, sixty percent of Republican Senators opposed his nomination. In contrast, every Republican Senator (and John Fetterman) supported Pam Bondi’s confirmation for AG, and all but two voted in favor of Kash Patel becoming FBI Director. The Senate, as currently configured, is the greatest threat to our republic.

J6 prompted several GOP officials to support Trump’s impeachment for “Incitement of Insurrection,” with ten House Republicans and seven Senators voting in favor. (The book incorrectly lists the House GOP leader—Kevin McCarthy– as one of the ten; he, along with Young Kim, Michelle Steele, and Ken Calvert, voted against impeachment.) After J6, there was hope that many Republicans would move beyond MAGA. The momentary reduction of MAGA extremism within the Republican Party, however, did not last. Garland’s careful strategy would be overshadowed by the quick return of Trumpism’s rampant deception and fraud.

Mistakes made prior to his confirmation on March 21 placed Garland at a disadvantage. On January 6, the FBI decided against making mass arrests, which meant they later had to use informants and gather evidence to find suspects who had already departed from the scene. The fake electors scheme, led by Chapman University’s John Eastman and UC Irvine’s Peter Navarro, was not revealed until after January 6 and was overshadowed by efforts to apprehend the capitol rioters. While targeting violent crimes at the Ellipse with clear evidence was logical, the electors scheme provided a simpler way to reach key January 6 planners. But that was not the path Garland chose.

The fake electors scheme consequently fell under the jurisdiction of state prosecutions. Although this approach prevented criminal convictions from being subject to presidential pardons, it also resulted in difficulties for prosecuting offenders operating at the highest level. It was, after all, a national scheme.

Not pursuing the fake elector scheme offered protection to Trump and his inner circle, with Roger Stone being a notable example. For decades, Stone has worked as a self-described dirty trickster for Republican candidates and was spotted with Oath Keepers around the time of the January 6 Capitol attack. There was ample evidence at the time that has been confirmed subsequently that the Oath Keepers played a lead role in organizing the J6 events. Other clues also pointed to roles played by close Trump supporters Ali Alexander and Alex Jones in supporting the attempt to overturn the results of the election. J. P. Cooney, a longtime Department of Justice prosecutor, proposed launching an investigation into the Oath Keepers’ involvement and to follow the money trails that could reveal those who supported their actions on January 6. However, this initiative was blocked.

Matt Axelrod, a former Obama DOJ appointee who helped supervise Biden’s transition, opposed a swift investigation into the Oath Keepers and its funders. Consequently, although multiple members of the Oath Keepers faced charges related to rioting and coordinating the attack on the Capitol, a targeted inquiry into the organization’s specific involvement did not materialize during the critical initial phase of the January 6 investigation. This lack of decisive action established the initial direction for the Biden administration under Attorney General Merrick Garland.

When Trump issued his blanket pardons of virtually all January 6 rioters on his first day in office in 2025, the fallacies of Garland’s DOJ came into full view. The countless hours of investigation and prosecution of nearly 1600 convicted criminals collapsed with the stroke of a Sharpie. Trump got away with sedition in 2021, and that is partially attributable to the failures of Garland.

Garland appears to have perceived his role as similar to that played by the justice department after Watergate. Many among our country’s elite believe that the U.S. Constitution survived Nixon’s actions unharmed, and that keeping the DOJ apolitical was essential to restoring order after January 6. Leonnig and Davis cite this as a reason for Garland’s cautious approach to J6 prosecutions, but do not address whether Watergate and Trump’s election denial are truly comparable. Still, it’s important to reject the misconception that Watergate left the Constitution undamaged. This book shows that problems linked to Trump stem from unresolved issues originating with Nixon.

Investigations into leaders of groups like the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys for seditious conspiracy were delayed too long. Michael R. Sherwin, who served as Acting US Attorney for the District of Columbia, recommended this proactive strategy. He foresaw that focusing mostly on the easily prosecuted cases—due to the abundance of evidence after January 6th—could overshadow the pursuit of much more important cases amid a flood of less significant ones. Focusing on less complex cases wasted resources, while important evidence was lost over time. The organizers of January 6 had time to conceal evidence establishing and coordinating alternative defenses. Prompt and decisive prosecution could have incentivized at-risk individuals to pursue plea agreements.

Sherwin, however, had committed the unpardonable sin in Garland’s DOJ. He boldly stated in a March 22 Sixty Minutes interview that additional seditious conspiracy charges might be brought against some current detainees. While Sherwin violated DOJ disclosure policy during ongoing investigations, the DOJ should have focused on more significant issues given his excellent initial work and his unique understanding of the complexity of January 6. Nevertheless, they proceeded to pursue Sherwin. The department filed complaints that could have risked his ability to practice law. The Department of Justice responded excessively to an honest mistake made by a capable and highly regarded prosecutor under unusual circumstances. Fortunately, New York and Ohio determined that the evidence was not sufficient to warrant Sherwin’s disbarment.

Garland’s DOJ devoted too many resources to minor cases by prioritizing easier ones. Prosecution was highly centralized and bureaucratic, leading to wasted time on reports to Garland’s closest assistants. Hesitancy among remaining Barr-era Justice

Department officials further complicated investigations into Trump associates. Consequently, a comprehensive investigation into the connections between Trump’s associates and the various militias present at the Ellipse on January 6 did not occur.

The FBI also hindered effective prosecution. FBI agents, especially those working in rural areas in Red States, engaged suspects with extraordinary deference, revealing their partisan and even racial bias toward perpetrators. Political divisions within the FBI hindered coordination between DC and distant regions. By May, representatives such as Republican Congressmen Thomas Massie and Chip Roy expressed concerns regarding what they described as the heightened politicization of the investigation. Political support for investigating J6 was fading both within the FBI and among the public at large.

The passage of time thus worked against Garland’s probe. After Senate Republicans acquitted Trump on impeachment for the second time on February 13, he appeared on FOX and other conservative media to argue the events were simply a protest by his supporters who had legitimate concerns over election integrity. Other parts of the far-right media sphere promoted the notion that violence had been instigated by the “Deep State” or Antifa. Not only did Republican Senators fail to impeach Trump, but they also filibustered Pelosi’s attempt to set up an independent commission to study the events of J6. Within weeks of J6, Trump had re-emerged as the defining figure of the Republican Party.

The more Republicans accused the DOJ of partisan prosecution, the more Garland moved to avoid the appearance of it. He did not pursue the strong evidence of Trump’s interference in Georgia’s election, instead leaving that investigation to state prosecutors. He was slow to react to increasing evidence of “a coordinated, multi-state effort to cast doubt on the 2020 election and undermine the electoral vote process.” [163]. These are both cases that would have compelled investigation of major figures and donors in the Republican Party.

Instead, the investigations spent inordinate time and resources on relatively insignificant cases. Garland ignored Sherwin’s suggestion to let nonviolent offenders plead out, thereby preventing increased attention on major cases. Critics of Garland in the Department of Justice viewed the choice to have the Georgia cases handled by state and local authorities as a political move. They believed this decision diminished the strength of those cases and hindered their efficient integration into federal prosecutions. The same critics noted that communications between Oath Keepers and Proud Boys clearly fulfilled the criteria needed to charge them with seditious conspiracy, especially in Stewart Rhodes’s case. Crucially, sufficient resources were not allocated to carefully examine the extensive financial records and other evidence that could have substantiated conspiracy allegations against key organizers and funders.

Garland, moreover, failed to embrace the opening handed to him during the impeachment trial in the Senate. On February 13, Mitch McConnell said Trump was “practically and morally responsible” for the attack but voted against conviction in the Senate, instead deferring accountability to the DOJ. This outcome was expected given McConnell’s established patterns of cowardice and unprincipled politics throughout his career. Responsibility was thus delegated to Garland, who subsequently assigned it to officials within the Department of Justice. Approximately seven months into his term, Garland had not undertaken a systematic investigation of Trump’s direct involvement in efforts to challenge the outcome of the election.

Pelosi Lights a Fire

Despite unsuccessful attempts to secure Republican backing in the Senate for a bipartisan investigation, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi formed a temporary committee dedicated to examining the events of January 6. She declined to seat Jim Banks and Jim Jordan on the panel, instead choosing Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger for the bipartisan committee. Banks and Jordan had been fully complicit in the events of January 6 and are clearly not honorable people. In mid-August, she assembled a team led by ex-DOJ attorney Tim Heaphy, mostly made up of Gen X lawyers, to run a parallel investigation to the one being pursued by the DOJ. Unlike the DOJ, this group quickly investigated the “alternate electors” plan devised by John Eastman.

Attorney Dan George from Heaphy’s team realized the importance of the scheme before January 6 and noted the large turnout of Trump supporters in Washington on that day. George thought Trump saw the fake electors plan as a way to create chaos and keep power. A coordinated plan involving “alternate” electors is evident from the systematically prepared and uniform certificates submitted fraudulently by Republicans in battleground states. A central figure in this scheme was Steve Bannon, who on January 5 had predicted that “all hell is going to break loose.”

Bannon’s testimony was crucial, yet he evaded criminal contempt charges for defying a House committee subpoena because the DOJ delayed taking action or sought to avoid appearing politically biased. While the DOJ hesitated to prosecute Bannon, both Biden’s White House and Congressional Democrats grew increasingly frustrated by this lack of resolve. Nevertheless, issues extended beyond the DOJ alone.

Biden delayed nominating appointees for the DC U.S. Attorney’s office and Assistant Attorney General for National Security, largely because he had to navigate such a treacherous path through the Senate confirmation process. Eventually, the President nominated Matthew G. Olsen for the National Security spot and Matthew Graves for the DC U.S. Attorney. Senate Republicans, notably Ron Johnson, then hindered these confirmations. The National Security Division was vital since the FBI Director, Christopher Wray, identified January 6 as a domestic terror investigation.

The Case Against the Oath Keepers

Meanwhile, journalism also appeared to be running ahead of Garland’s DOJ. In October, Bob Woodward and Jim Costa of The Washington Post reported a command center at the Willard Hotel involving Roger Stone, his Oath Keeper escorts, Rudy Giuliani, Steve Bannon, Bernard Kerik, and John Eastman. Eastman had mentioned in May that the Willard meetings served as planning meetings. Kerik billed the Trump campaign over $55,000 for legal team lodging at the Willard during the two weeks

before January 6. This type of reporting prompted the House Select Committee to launch focused investigations into persons directly tied to Trump. In contrast, the Department of Justice maintained its focus on those at the Ellipse who committed easily provable crimes. This reluctance to investigate the planners frustrated prosecutors in the AG’s office.

There were multiple factors contributing to this hesitation. The Department of Justice’s concern about the perception of political bias hindered effective collaboration with the House Select Committee. As a result, the DOJ lagged the House investigation and depended largely on publicly available findings. The FBI was cautious about probing politicians and their associates, even hesitating to request subpoenas tied to the Willard Hotel meetings. The Assistant Director of the Washington Field Office recognized the complexities associated with overcoming First Amendment protections for the group assembled at the hotel. DOJ prosecutors were frustrated that privacy concerns for hotel guests outweighed the value of potential evidence from subpoenaed records about the Oath Keepers.

Neither FBI Director Chris Wray, appointed by President Trump, nor Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco, appointed by President Biden, would authorize focusing the investigation on individuals directly associated with former President Trump. The investigation focused exclusively on members of the Oath Keepers, rather than on individuals like Roger Stone and John Eastman, who were more directly connected to Trump. After the publication of the Woodward and Costa piece, on December 16, 2021, AG Garland finally agreed to proceed with seditious conspiracy charges against Steward Rhodes and twelve other Oath Keepers.

Persuading the DOJ to pursue seditious conspiracy charges against the Oath Keepers was difficult due to minimal legal precedent. Even with a D.C. jury’s potential conviction, an appeal to the Supreme Court would face significant free speech and association protections under the U.S. Constitution. As is shown repeatedly in this story, SCOTUS is where justice goes to die.

Nevertheless, it was evident that the time was right for DOJ to act more aggressively. The Select Committee discovered fresh evidence concerning Mark Meadows, who served as Trump’s Chief of Staff. Additionally, audio recordings of Fox News hosts urging the White House to halt the Capitol attack had become public and cast Trump in a negative light in public opinion.

The delay in prosecuting the Oath Keepers hampered the broader investigation. Had it started sooner, it might have led to plea agreements that implicated individuals more directly connected to Trump. Fear of a SCOTUS dismissal could have revealed the political biases of its members and challenged the public’s perception of their impartiality. Notably, seditious conspiracy charges were only brought nine months after Sherwin publicly suggested their suitability in his March Sixty Minutes interview. Clearly, this delay resulted in lost valuable time. Ultimately, the cases would move forward in a manner that distinguished the culpability of the Oath Keepers from that of their associates at the Willard Hotel. Simply put, the main parties at fault were let off.

The Fake Electors Scheme

Failure of the DOJ to investigate the “alternate electors” scheme also lost valuable time. Evidence of the alternate electors scheme remained mostly unexamined in DOJ archives for over a year until an interview with Michigan AG Dana Nessel prompted systematic investigation. In a subsequent CNN interview on January 25, 2022, Lisa Monaco broke news when she referenced an ongoing investigation into the electors scheme. The slow process of drawing subpoenas for the eighty-four signatories to the scheme could at last begin.

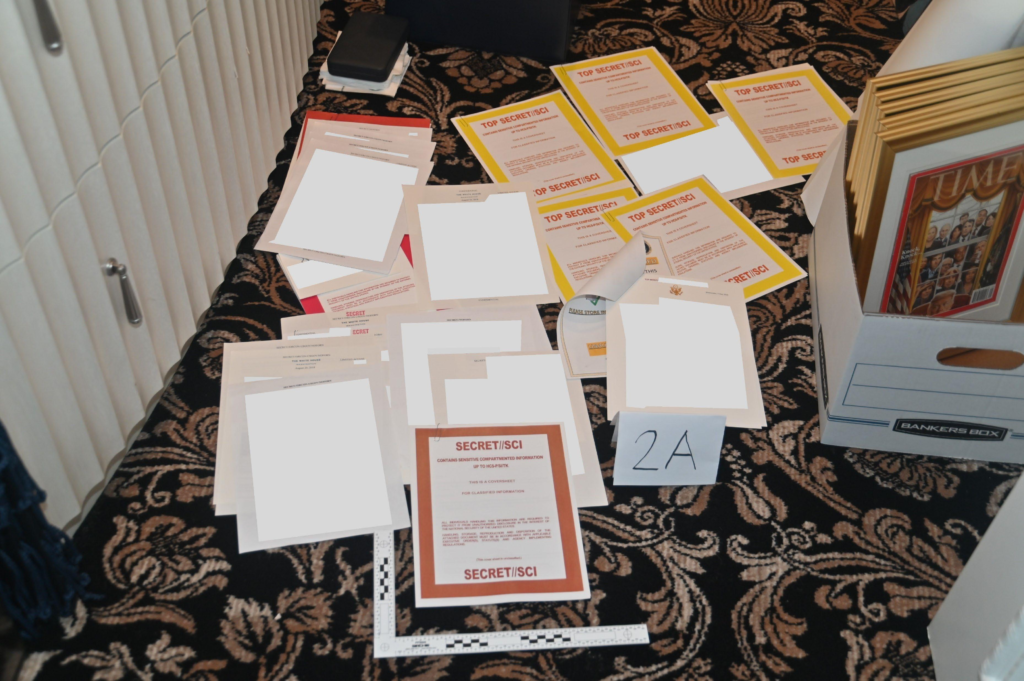

The Theft of Classified Documents

After the DOJ started investigating the electors scheme more than a year after January 6, the National Archives discovered that Trump had taken dozens of boxes of highly classified US documents. Although classified materials had been removed from secure locations before, the volume and variety of sensitive documents that Trump transported to Mar-A-Lago was unprecedented. Classified materials appeared haphazardly distributed among unclassified materials in unsecured locations. It is important to note that these materials remained unsecured for over a year. FBI counterintelligence agents were shocked to learn about this.

When The Washington Post reported on the classified documents on February 7, 2022 Congressional Democrats and members of the liberal media expressed concern regarding the perceived delays in the Department of Justice’s operations. Many recall the FBI controversy over Hillary Clinton’s use of her personal computer for government emails. Trump’s abuse of handling of classified documents was even more disturbing.

Eastman: The Serpent in Trump’s Ear

While the DOJ lagged, the House Select Committee continued to make significant progress in pursuing a seditious conspiracy charge against former President Trump based on a ruling issued by Judge David O. Carter in a California federal court o

March 28, 2022. In this case, John Eastman claimed that the Select Committee’s demand for his emails would violate attorney-client privilege; however, this assertion was widely regarded as legally specious. Judge Carter rejected the privilege assertion and immediately questioned why the Committee had not pursued the crime-fraud exception if it was investigating sedition. On March 28, Judge Carter made a clear statement in his decision, describing Trump and Eastman’s actions as “. . . a coup in search of a legal theory.”

His ruling criticized the DOJ, questioning why they had not acted given the compelling evidence. Leonnig and Adams cite the ruling directly:

“More than a year after the attack on our Capitol, the public is still searching for accountability. This case cannot provide it,” Carter wrote. “If Dr. Eastman and President Trump’s plan had worked, it would have permanently ended the peaceful transition of power, undermining American democracy and the Constitution. If the country does not commit to investigating and pursuing accountability for those responsible, the Court fears January 6 will repeat itself.”

[p. 228]

These remain prophetic words today. The extent to which Judge Carter’s ruling influenced the April 14 decision of the FBI and DOJ to finally devote proper resources to the electors scheme is unclear.

The House Select Committee clashed with the DOJ over jurisdiction and declined to share its findings after the DOJ finally began investigating the elector scheme. Although congressional investigations seldom surpass what the DOJ uncovers, this investigation clearly did so. The DOJ’s limited investigation into the electoral conspiracy after 15 months was a major flaw. Relying on the findings of the House Select Committee, which had only started its investigation in July 2021, would clearly address the gaps left by the lapsed DOJ investigation. Any collaboration between these two distinct yet coequal branches of government, however, would likely have presented significant legal and political challenges. Chairman Bennie Thompson and Vice Chair Liz Cheney vehemently opposed sharing their hard-earned findings with the DOJ.

The Department of Justice encountered a unique set of obstacles when handling the issue of classified documents at Mar-A-Lago. Garland was inclined to take a stronger approach but ran into hesitance from the FBI, partly due to the fallout from the Clinton investigation and the Crossfire Hurricane probe into Trump’s connections with Russia. The most significant hurdle, however, was Trump’s cunning behavior. He insisted, incorrectly, that all presidential records created during his time in office belonged to him personally, rather than being public property. Additionally, he claimed executive privilege over these records, despite such protection only applying while serving as president.

Trump was also adept at misleading both lawyers and aides, which made it difficult for federal agents to determine exactly what kinds of records—and how many—he kept at his Florida and Bedminster properties. To further complicate matters, he had his aide Walt Nauta coordinate a series of document transfers, essentially playing a shell game with around 90 boxes of records to prevent DOJ prosecutors from discovering them. Say what you will about Trump, he is a very sophisticated liar.

Problems in the classified documents case became apparent on June 2 when the FBI executed a highly restrictive search warrant that was based on inaccurate information Trump had given to his own lawyers—information they failed to verify. When agents arrived to conduct the search, Trump had told his lawyer to allow them access to all the boxes. However, counsel for Mr. Trump advised the agents that examining the contents of those boxes would constitute a violation of the warrant’s stipulations. Upon observing the storage room on June 2, the agents noted that both the quantity and arrangement of the boxes differed from those depicted in a photograph previously supplied by a Trump aide several weeks earlier during a preliminary interview. This discrepancy would have to be investigated.

Cassidy Hutchinson

Three weeks after this search, the House Select Committee investigation would again take center stage with the explosive testimony of Cassidy Hutchinson. She was the young aide to Trump’s Chief of Staff, Mark Meadows. She directly witnessed much of Trump’s actions on January 6 and also communicated frequently with Meadows through texts and emails during that period. She saw Trump react angrily after Barr told the AP there was no evidence of major election fraud to overturn Biden’s win. This resulted in a situation where she felt obligated to clean up the Oval Office wall after President Trump reacted to Barr’s statement by throwing a ketchup tantrum. She knew Trump had insisted his supporters bypass the magnetometers at the Ellipse because he was aware they intended to target others, not himself. She was also aware that Trump ignored pleadings from Meadows and Ivanka that he tell the rioters to retreat. Her testimony stunned the public.

Hutchinson’s testimony further underscored the disparity between the slow pace of the Department of Justice investigation and the advances made by the Select House Committee. By the time DOJ prosecutors contacted Meadows’ attorney to request access to his texts and emails, the committee had been in possession of those materials for six months. The DOJ had never heard of Cassidy Hutchinson prior to her public revelations on June 28. Put simply, the many lawyers at the DOJ were discovering information about an event from eighteen months earlier at the same time as everyone else. Although it was clear that the committee’s disclosures to the public could complicate DOJ prosecution, the Department of Justice was responsible for its initial strategy and decision not to engage discreetly with the committee six months prior.

Although Leonnig and Davis are exceptionally thorough reporters, their summary of Hutchinson’s testimony includes an interpretation that warrants further scrutiny. On page 260, they claim that Hutchinson’s testimony intensified frustration among “the left,” highlighting once more what they see as the DOJ’s inadequate prosecution efforts. Meanwhile, “the right” described these developments as additional evidence that Garland was acting on behalf of the Democrats. This situation, though, is not simply about two opposing groups interpreting the same evidence differently. Instead, it involves one side considering evidence presented through credible testimony by individuals closely involved in the Trump administration, while the other side depended on Trump’s statements and coverage from easily discredited sources like FOX News and Newsmax. One group was relying on facts, while the other was spreading and believing easily provable lies.

This ideological framing is particularly unsuitable when considering Liz Cheney’s unique contribution in deftly handling the difficult legal and politically challenges involved in bringing Cassidy Hutchinson’s testimony to light. While Cheney is undeniably aligned with the political right, she demonstrated unmatched bravery, integrity, and principle throughout this process.

Although Hutchinson’s testimony presented certain challenges for the DOJ, it ultimately motivated the department to pursue prosecution more assertively than before. Imagine if there had been a House Select Committee for the classified documents case!

The Mar-A-Lago Search

The Department of Justice decided to obtain a subpoena for searching Mar-A-Lago without informing former President Trump, after the FBI determined that he had given them and his own legal counsel incorrect details about the amount and location of classified documents. The DOJ first requested and received surveillance footage from Mar-A-Lago through a polite request to Trump’s lawyers. When they reviewed these tapes, they discovered that aides had moved many boxes to unknown places before DOJ officials visited in June. This suspicious behavior warranted a broader search subpoena, though the FBI was still initially hesitant to move forward with the search.

Although Leonnig and Adams do not explicitly assert this point, there seems to have been a notable tendency within all levels of the FBI to provide protection to Trump due to political considerations. This reluctance to prosecute Trump is especially evident with Steven D’Antuono, Assistant Director of the FBI’s D.C. Field Office. Both he and several field agents often voiced reluctance to prosecute a former President. However, Trump was not just any ex-president; he had been impeached twice and faced numerous substantiated criminal accusations. Too many in the FBI appeared willing to overlook that fact. As a result, an unusual situation arose within the DOJ: prosecutors advocated for a more assertive stance, while the FBI recommended greater caution. D’Antuono finally relented, but not without making his opposition known.

Once the FBI had completed its search on August 8, 2022 Trump and his Fox News propagandists proceeded to lie about what had happened. FOX aired a grainy nighttime video showing an alleged FBI agent with a long gun standing among palm trees. This was old stock footage and the agent in the video was clearly a U.S. Secret Service officer. Trump went on to claim that the FBI had broken into his safe. Also, not true. Hysterical Trump supporters began to threaten the FBI on-line. Members of Trump’s inner circle released the paperwork from the search warrant to reveal the names of the agents involved in the search as well as the judge who signed the warrant. These are names that the FBI had redacted from the papers submitted for public consumption. Trump sued the FBI two weeks later, alleging political motives behind the investigation.

Trump benefited from having his appointee, Judge Aileen Cannon, preside over the documents case. He requested that she designate a special master to review the seized documents, which would consequently postpone the investigation. No serious judge would have considered such a request, but Cannon is not a serious judge. She gave the DOJ ten days to respond.

This put the FBI back in its usual role as the aggressor for the DOJ. They advocated that the public now be made aware of the damning evidence that was found in the search. In addition to credible testimony documenting several occurrences of dishonesty, photographic evidence was also presented. Photos revealed that Trump possessed classified documents, contradicting his lawyers’ statements to the DOJ that only personal and Presidential records were stored securely. These photos were made public on August 30. Everyone except Fox News viewers and Aileen Cannon could readily see Trump’s lie.

Jack Smith

By September, the DOJ had strong evidence against Trump in both the January 6 and documents cases, but Garland outrageously chose to delay action for two months before the 2022 midterms. He cited a DOJ policy discouraging public investigation within two months of Election Day, even though Trump was not yet an official candidate. This confounded DOJ prosecutors. Garland explained that since Trump was clearly the leader of the Republican Party in 2022, avoiding any perception of bias against Republicans in Biden’s DOJ was essential. After a two-year investigation, the DOJ was already behind schedule, and more delays would help the defense. It also raised questions about how the DOJ would respond if Trump officially became Biden’s opponent.

This situation raises the question of why Garland would choose to delay appointing a Special Prosecutor until after Trump’s announcement, given his prior acknowledgement of Trump as the leader of the Republican Party. He effectively rendered the Department of Justice inactive and transferred authority over the timing and manner of prosecution to Trump.

Garland had Jack Smith appointed as Special Counsel on November 15. DOJ prosecutors familiar with Jack Smith’s work were thrilled when he was appointed three days later. Some were concerned, however, that he had been assigned to both the January 6 investigation as well as the classified documents case. Managing both involved significant legal and political risks.

Jack Smith’s appointment as Special Counsel promptly energized the investigations into the efforts to overturn the 2020 election and the classified documents case. He quickly organized and led these inquiries, efficiently assembling a team of seasoned prosecutors. The Special Counsel was able to conduct their investigation without having to worry so much about appearing politically biased. It is therefore worth considering why the appointment of this Special Counsel did not occur at the outset of the Biden administration.

The Special Counsel derived significant benefit from immediately obtaining the extensive evidence assembled by the House Select Committee, even though the circumstances were not ideal. After Republicans resumed control of the House in the 2022 midterms, the committee knew that its worked had to wrap up quickly. House Committee prosecutors and aides worked overtime to compile and transfer evidence to the Special Counsel’s office. Some of the House committee’s prosecutors took assignments with Smith.

The Special Counsel investigation focused on five main areas: the electors scheme; making false statements to state officials to try to change vote counts; attempts to misuse the Justice Department by installing Jeffrey Clark; exerting pressure on Vice President Pence; and inciting the Capitol riot to delay Biden’s certification. Additionally, the investigation investigated how financing was used to support these activities. The evidence gathered was substantial; however, the Special Counsel concluded that Cassidy Hutchinson’s testimony would likely not be admissible in court due to the number of witnesses who provided sworn statements contradicting her assertions. On the other hand, the Special Counsel could prove beyond a reasonable doubt that none of the scores of claims of election fraud made by Trump were true and that he knew it.

There were a couple of problems with Smith’s approach to the investigation. Although he relied on a close circle of trusted advisers, this often meant he missed out on perspectives from other capable prosecutors with expertise in important areas of the investigation. This was particularly true regarding classified documents, where specialists are scarce and their insight is extremely valuable. This problem played into one of the most fateful mistakes made by Smith.

Smith surprised many prosecutors by prosecuting the documents case in Florida rather than D.C., where judges are more familiar with classified materials. He believed Florida’s case law was more appropriate. David Raskin, a seasoned national security prosecutor, was especially shocked—particularly since Judge Cannon had previously displayed political bias, and most experts would have preferred the case be tried outside of her jurisdiction if possible.

Selecting Florida as the venue was a challenging decision for sure. Most of the evidence pertaining to the crimes was found in Florida. Relocating the trial to Washington, D.C., where juries would be drawn from a predominantly Democratic pool, could not only create an impression of political motives but might also provide grounds for a judge to overturn the verdict due to perceived bias in venue selection. That was Smith’s biggest fear. Smith recognized the challenges of trying the case in Florida, especially considering that Judge Aileen Cannon had a strong chance of being assigned. Statistically, there was a one-in-seven likelihood, but due to other judges’ full dockets, the actual odds were closer to one in three. While Smith seemed aware of these probabilities, he did not fully grasp just how problematic Judge Cannon’s appointment would be. Once she was selected, Smith made efforts to remain optimistic. Unfortunately, this meant that one of the most significant federal cases in two centuries ended up with a judge widely regarded as both incompetent and biased.

Smith possessed compelling evidence regarding the charges in the documents case. Not only was there substantial proof that Trump had misled his own lawyer, but also evidence that he directed aides to conceal boxes from both his attorney and federal investigators. Additionally, there was recording of Trump at Bedminster, boasting to visitors that he still retained a classified war-planning document. Based on this evidence, a grand jury of twenty-three members charged Trump on June 8 with thirty-three felony counts, including conspiracy to obstruct a criminal investigation, making false statements, and improperly handling classified documents.

Following Trump’s indictment in Florida for obstruction and mishandling classified documents, Special Counsel Smith also charged him with fraud related to efforts to overturn the 2020 election. Prosecutors faced challenges, including the strong free speech protections for political candidates and limited direct evidence that Trump knew he lost. Ambiguous remarks to family and staff raised doubts about whether Trump truly believed his claims or was intentionally misleading. Was there clear evidence of deceit, or were his actions due to genuine delusion? It is always hard to tell with pathological liars.

Smith filed the indictment for electoral fraud on August 1, 2023. The opening statement alleged the Defendant knowingly made false claims of election fraud and victory. The charges included four counts of civil rights violations, two counts of obstructing congressional certification, and one count of conspiracy to defraud the United States. These claims against a former president were unprecedented and compelling. They would never be brought before a jury.

“With Fear for our Democracy, I Dissent.”

Nearly one year later, on July 1, the Supreme Court ruled that presidents have broad immunity from prosecution for nearly any crime committed while in office. Chief Justice Roberts foresaw the case against Trump as setting a precedent in which a President could pursue vindictive prosecutions against their predecessors once they were in office. Justice Roberts appears unconcerned by the precedent set under his leadership, when the U.S. failed to peacefully transfer presidential power for the first time.

The Roberts court’s decision reversed a lower court’s rejection of Trump’s claim to executive privilege. On February 6, 2024, an appeals court had dismissed Trump’s assertion of unlimited executive authority, stating it would place the president above the other two branches of government. The judge asserted, moreover, that Trump’s claims would allow any president to challenge the results of any election without consequence.

Chief Justice Roberts quickly made his disagreement with the lower court’s ruling clear. He expressed strong private criticism of the appeals court’s decision and told the New York Times that the Supreme Court planned to address the separation of powers issue differently. He articulated the central question of the case as follows: “Whether and if so to what extent does a former president enjoy presidential immunity from criminal prosecution for conduct alleged to involve official acts during his tenure in office.” [335] It is a convoluted question, an obfuscation ideal for his casuistic court and its biased minions of law clerks.

The main defense arguments focused on the idea that presidents are often required to make crucial decisions during significant national security threats, and therefor following standard legal procedures too strictly could limit their ability to manage such crises. This perspective implies that, in certain ways, a sitting president should be considered above the law in prescribed circumstances.

Roberts stated that impeachment, not the Department of Justice, is the most effective check on executive power abuses that might fall into this category. He should know. He presided over two impeachment hearings during Trump’s first term.

One big problem, though. During the impeachment proceedings both Trump’s attorney and Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell argued that impeachment was unnecessary because presidential accountability could be maintained through the Department of Justice. They argued that responsibility for presidential accountability as it related to January 6 should fall to the Attorney General. Now that Trump is being prosecuted by the DOJ, however, his attorneys had no problem changing their argument completely.

Before the Supreme Court, President Trump’s legal team contended that the Department of Justice is precluded from investigating the President, as doing so would infringe upon constitutionally protected executive privilege. Roberts and the six Republican appointees agreed. Trump’s legal advisors exploited the conundrum. Slate appropriately entitled its article on this: “The Most ‘Heads I Win, Tails You Lose’ Trump Argument Ever.” [p. 331]. Roberts thus seemed to play the role of circus master in a three-ring clown show.

At the Supreme Court hearing, a Special Counsel attorney began with a notably prophetic remark. He claimed that what Trump was seeking “would immunize former presidents from criminal liability for bribery, treason, sedition, murder, and, here, conspiring to use fraud to overturn the results of an election and perpetuate himself in power.” [338]. These are the five words that have come to describe precisely the character of Trump’s presidential legacy: bribery, treason, sedition, murder, and fraud.

Garland was profoundly shocked and hurt by the 6-3 court decision. He personally knew and respected many of the justices who supported the ruling. “They know this isn’t right,” the Attorney General confided to a friend. [341]

Justice Sotomayor wrote the dissent, with a statement for the ages:

“Orders the Navy’s Seal Team 6 to assassinate a political rival? Immune. Organizes a military coup to hold on to power? Immune. Takes a bribe in exchange for a pardon. Immune. Immune, immune, immune,” she wrote. ‘. . . Even if these nightmare scenarios never play out, and I pray they never do, the damage has been done.”

“In every use of the official power, the President is now a king above the law,” Sotomayor concluded. “Never in the history of our Republic has a President had reason to believe that he would be immunie [sic] from criminal prosecution if he used the trappings of his office to violate the criminal law. Moving forward, however. . .. If the occupant of that office misuses official power for personal gain, the criminal law that the rest of us must abide will not provide a backstop…

“With fear for our democracy, I dissent.” [342]

The importance of this ruling cannot be overstated. Following the ruling that broadened the application of executive privilege, nearly all the significant evidence gathered by the Special Counsel against Trump was rendered inadmissible. As a result, this evidence could not be presented to a jury or made public during the election period, which proved advantageous for Trump’s presidential campaign.

Trump’s Re-Election

The six SCOTUS Republicans and Aileen Cannon thus achieved their implicit goal. They ensured that the public would not see the powerful evidence compiled against Trump prior to the election. They hid the J6 and classified documents cases just as AG Barr did with the Mueller report on Trump’s Russia investigation. Their decisions allowed Trump’s campaign to absurdly claim that all three investigations were hoaxes carried out by corrupt Democrats conspiring with the deep state to keep Trump from making America great again.

The first three weeks of July thus established the context in which the rest of the campaign would unfold. On July 1, the Roberts court issued its ruling in the January 6 investigation. On July 13, former President Trump survived an assassination attempt in Butler, Pennsylvania. The incident provided iconic imagery for the campaign and led some people to view him as a providential candidate opposing sinister adversaries within the deep state. On July 15, Judge Cannon issued a ruling challenging the constitutionality of the Special Counsel’s office in the documents case, thereby delaying proceedings and excluding public scrutiny of the documents case for the duration of the campaign. On July 18, the RNC hosted its convention, celebrating MAGAdom, the symbolic earlobe, and a victorious candidate rejoicing over recent legal victories. On July 21, Biden would drop out of the race after a disastrous debate performance on June 28. Republican appointed judges thus had prepared the way for the return of Trump.

The courts’ decisions also had the effect of convincing 85 million voters that it was not worth their effort to vote. Rather than focusing on issues such as sedition or classified documents, the campaign would redirect its emphasis toward the anger, hatred, fear, and ignorance that Trump frequently exploits. Had “did not vote” been a candidate in he 2024 election, it would have won by a landslide in both the popular vote and the electoral college. About 4.4 million fewer people voted in 2024 than 2020. Apathy and disgust won the election.

Smith quickly overturned Cannon’s constitutional challenge to the Special Counsel, but failed to have her removed from the case, even after she began a misconduct inquiry against him and made several decisions clearly biased in favor of Trump. Cannon’s argument against the constitutionality of the Special Counsel was quickly dismissed since the Supreme Court had previously confirmed that the Attorney General has the legal authority to appoint a Special Counsel, as exemplified in the recent past by the appointment Archibald Cox and Leon Jaworski during the Watergate investigation.

Despite these setbacks, prosecutors in Smith’s office continued to pursue charges against Trump related to the January 6 case. His prosecutors refined their arguments by distinguishing between actions taken by Trump as a candidate and those undertaken during his presidency. As a result, four out of five charges were able to proceed, while the charge concerning the appointment of Jeffrey Clark as Attorney General proved difficult to pursue independent of considering Trump’s presidential role.

The major line of evidence that the Special Counsel’s office lost pertained to that which could prove that Trump must have known that he lost the 2020 election. “The case lopped off the warnings that senior leaders of the Justice Department, his director of national intelligence, senior officials at his Department of Homeland Security, and senior White House lawyers had consistently given Trump: He had lost the election.” [351] It would be difficult to prove beyond a reasonable doubt in a court of law that The Big Liar knew that he was telling The Big Lie.

Judge Tanya Chutkan, the US District Judge for the District of Columbia assigned to the January 6 case, did not let the political calendar influence the continuing proceedings. As a result, some evidence about the Big Lie continued to emerge during the campaign. Chutkan and Smith thus became part of that group that Trump labeled as “the “enemy from within.” During his campaign, he pledged to pursue their prosecution to the fullest extent permitted of the law once he returned to the White House.

Following Trump’s victory, the proceedings against him, as well as the evidence presented by Garland, Smith, and the Special House Committee, were rendered moot. By the end of November, Trump, FBI nominee Kash Patel and Attorney General nominee Pam Bondi were vowing to dismiss all “rogue bureaucrats” at the Justice Department who were involved in the investigations. On November 25, knowing that prosecuting a sitting president is not possible, Smith moved to drop all charges related to the January 6 and classified documents cases. Through no fault of his own, Smith was required to execute this significant miscarriage of justice. Conservative Justice John D. Bates admitted that it was a mistake not to present this evidence to a jury. He knew who to blame: “The judiciary failed the American people.” [356]

The Purge at the FBI

Soon after Trump’s re-election, Christopher Wray’s resignation as FBI Director sparked controversy. In 1976, Congress set ten-year terms for FBI directors to ensure the agency’s independence from presidential political influence. If Trump had been made to fire Wray, some congressional Republicans might have faced pressure to support FBI independence and endorse checks and balances. Appointed as FBI director by Trump in 2017, Wray understood that engaging in a prolonged political dispute with Trump would only add more stress and uncertainty for bureau agents. He therefore resigned.

Wray was likely right. In the initial period of the second Trump administration, congressional Republican majorities showed few signs of having an identity separate from their MAGA leader or demonstrating any dedication to upholding the law or the constitution.

With Trump back in office, experienced FBI personnel quickly realized their office could not stay out of political affairs. Prior to the Senate Republicans’ confirmation of Kash Patel as FBI Director, Wray endorsed Brian Driscoll for the role of Acting Director. Upon Patel’s confirmation, Driscoll was anticipated to continue serving as Deputy Director. But Driscoll represented a level of independence that would not be tolerated under Trump 47.

The politicization of the FBI became abundantly clear in the interview of Driscoll led by Paul Ingrassia, Trump‘s liaison to the DOJ. Ingrassia began the interview by asking Driscoll whom he had supported in the presidential election, if he had voted for any Democrats over the past five years, and whether he would be willing to act against people involved in the January 6 investigation. Driscoll clarified to Ingrassia that the job interview was for a DOJ agent role, not for a cabinet position. “This is not something an FBI agent should be answering,” Driscoll said. [362]

This content of this mid-January interview helps explain President Biden’s January 19 pardons for individuals targeted by Trump. These included former chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Mark Milley, whom Trump had threatened to execute for treason. It also included various members of the January 6 committee as well as Anthony Fauci.

Mass dismissals, reassignments, and demotions commenced promptly. Executive Order 14147, signed by President Trump on January 20, authorized the removal of FBI agents. Fifty intelligence officials who had signed a 2020 letter expressing doubts about the authenticity of Hunter Biden’s alleged laptop emails had their security clearances revoked without delay. A week later, Trump requested a list of prosecutors investigating him to have them dismissed. Emil Bove asked Driscoll to put together the list, but Driscoll declined. Bove said he was acting on instructions from Patel, who had not yet been officially confirmed in his position. Notably, while Bove was pressuring Driscoll, Patel was assuring Senators that there were no plans to remove large numbers of FBI agents who had worked with the Special Counsel’s office. If Driscoll’s claim was true, Patel had lied under oath in his confirmation hearing.

Besides jeopardizing the careers of DOJ officials, Trump also nullified their successful prosecution of nearly 1,600 January 6 rioters through sweeping pardons. These individuals comprised those convicted by unanimous jury verdicts of violent crimes, including numerous repeat offenders who engaged in additional acts of violence following their receipt of pardons. Trump also issued pardons to Enrique Tarrio from the Proud Boys and Steward Rhodes from the Oath Keepers, each of whom had been found guilty of seditious conspiracy by a jury and given sentences of approximately twenty years each. These charges had been serious and difficult to prove in court. Countless hours of investigation and prosecution went to waste as one of the first acts of Trump 47 was to pardon convicted, violent, and seditious criminals.

Driscoll continued to withhold the names of agents involved in the Special Counsel investigation, causing frustration for Bove as well as Trump’s deputy adviser, Steven Miller. Bove issued a mandatory survey to FBI management, demanding the identification of employees participating in the January 6 investigation. Rather than complying with Bove’s deadline for survey completion, the FBI Agents Association initiated legal action to prevent the disclosure of agents’ names. On August 8, Trump dismissed Driscoll and several other FBI officials who would not supply a list of agents working on the January 6 investigation. Driscoll and the other senior officials have since filed a lawsuit claiming that their terminations violated both federal law and their constitutional rights.

Trump and the Mayor of New York

The quid pro quo between Trump and New York Mayor Eric Adams prompted loyalty tests, resignations, and threats of demotion or dismissal in Trump’s DOJ. The Acting U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York possessed substantial evidence that Adams received illegal gifts from wealthy Turkish citizens in exchange for persuading city fire officials to ignore construction safety regulations during the construction of a Turkish consulate. The SDNY also had evidence that Adams accepted bribes, destroyed evidence, and pressured others to do the same. Danielle Sassoon, who is a conservative lawyer and a friend of Bove, was appointed to lead the SDNY on January 21. Trump seemed interested in working with Adams, a Democrat known for criticizing Biden’s immigration policy. By keeping Adams in his position, Trump found justification to enforce strict crackdowns on immigrant communities in New York. Additionally, there are advantages to having the mayor of New York in a vulnerable situation.

Sassoon, however, would not comply. On February 10, news leaked that Bove had ordered her to dismiss the Adams case. The public in New York was already aware of the allegations, so abruptly dropping the case against Adams likely would have caused public uproar. Sassoon viewed Bove’s demand as coercive misconduct and a misuse of the criminal justice process. She offered to resign instead, which also became leaked to the public. On February 13, Sassoon resigned. Bove had failed in the SDNY and turned to the Public Integrity Section (PIN) of Main Justice in D.C. to get the Adams case dismissed.

The supervisors at PIN also frustrated Bove. The attorneys specializing in public corruption chose to resign one after another to uphold the integrity of their office. In a moment of anger, Bove informed around two dozen trial attorneys at the DOJ that they needed to join a mandatory video meeting within an hour. During the call, he insisted that at least two lawyers volunteer to drop the charges against Adams, allotting them just one hour to decide. The possible rewards and consequences were clear without being stated: those who agreed to file the motion could feel confident about keeping their jobs and might even anticipate a promotion, while anyone who refused to participate or cooperate risked losing their position. Alternatively, they could all resign at once.

Mass resignations were the favored option of all on the call, but that could come with difficult consequences: near retirees risked reduced pensions, experienced staff risked losing security clearances and opportunities for promotions, and younger attorneys could lose access to top career paths. Another key issue was the fate of ongoing prosecutions if they resigned.

A PIN supervisor who was close to retirement offered to approve dropping the charges against Adams as a solution to the problem that Bove had imposed on them. Ed Sullivan, the volunteering supervisor, had prior experience with setbacks and thus little left to risk. Sullivan needed to draft a dismissal order that did not undermine the SDNY’s integrity. It was a thankless and impossible task, but he did it anyway. Bove promoted Sullivan to be the chief of PIN. Sullivan’s standing among colleagues at SDNY as well as with individuals in PIN who were not part of the inner circle, however, plummeted.

The Adams case dismissal has many parallels to the more recent pardon of Texas Democratic Representative Henry Cuellar. Cuellar and his wife were indicted for accepting $600,000 in bribes from an Azerbaijan oil company and a Mexican bank. Shortly after the publication of Injustice, Trump pardoned Cuellar and his wife before their case went to trial. Trump cited Cuellar’s criticism of Biden’s border policy as a reason to pardon him of crimes for which he had been indicted.

There may, however, be more to the Cuellar story than the quid pro quos on immigration policy. There is a global pattern to Trump’s corruption that frequently involves the nexus between Moscow, Riyadh, Ankara, Baku, and Tel Aviv. Leonnig and Adams do not address this, but it’s possible these pardons involve issues even more troubling than Trump’s border policy.

“The Homegrowns Are Next.”

The final chapter of this powerful and unsettling work fittingly examines how the justice system’s infrastructure fell apart in connection with the Kilmar Abrego Garcia case. This case shows the erosion of core constitutional principles like due process, separation of powers, and protection against cruel and unusual punishment. It represents the enthronement of tyranny sanctioned by the six Republican appointees on the Supreme Court in its “absolute immunity” decision of July 1, 2024.

James E. Boasberg is a central figure in the Abrego Garcia case. Judge Boasberg, appointed by Barack Obama and unanimously confirmed by the Senate, faced criticism from Trump and Republicans after questioning whether Homeland Security could deport Abrego Garcia to El Salvador without a court hearing. Abrego Garcia had entered the U.S. without documentation but had in the meantime obtained temporary protected status on the reasonable claim that he would not be safe in El Salvador.

Rather than comply with Judge Boasberg’s directive to grant Abrego Garcia a court hearing before deportation, the Trump administration chose to ignore it. Trump asserted that he possessed the authority to challenge a federal judge’s orders by invoking wartime emergency powers. Instead, DHS put him on a plane to El Salvador, where he would be placed in a concentration camp. Judge Boasberg directed DHS to return Abrego Garcia immediately.

Following criticism from Trump, Congressional Republicans moved to impeach Boasberg. Boasberg’s impeachment also involved charges concerning his approval for prosecutors to access Republican Senators’ phone records as part of the “Arctic Frost” investigation into bribery and illegal campaign donations from oligarchs and foreign governments connected to Russia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey. (A common pattern appears to be emerging here!)

Chief Justice Roberts seemed uneasy with the evident disregard shown by both the legislative and executive branches for Boasberg’s orders. Roberts issued a statement claiming to support the authority of judges to uphold essential constitutional principles, but his words came across as hypocritical. Roberts was, after all, the person most responsible for instituting absolute immunity in the executive branch.

Acting like a man with absolute immunity, Trump used the Abrego Garcia case to justify further abuses of power. When Judge Boasberg learned that Abrego Garcia had been incarcerated in El Salvador, he demanded that the Trump administration return him to the United States. Trump and the Salvadorean dictator Nayib Bukele then proceeded to deny that they had any authority to do anything in relation to releasing Garcia. Trump absurdly stated he lacked power over Bukele as the leader of another country, and Bukele asserted he could not interfere with his own state’s judicial system. Individuals such as Abrego Garcia became subject to an expanding scope of extrajudicial executive authority. Trump expressed satisfaction, claiming he could use these legal ambiguities to his advantage. He urged Bukele to construct more prisons for anticipated needs. “The homegrowns are next,” he told the Salvadorean dictator.

The book also concludes by documenting the widespread early capitulation to Trump’s authority, especially within the legal field. Major law firms have paid Trump millions in uncontested settlements to protect attorneys with potential conflicts involving Trump or his supporters. These firms aim to maintain access to classified documents related to their major cases and to continue to qualify for government contracts. This act of appeasement placed an even greater burden on principled law firms that refused to yield to such blackmail. Similar capitulations have occurred in media, education, science and technology, and elsewhere. This book, however, sustains a singular focus on justice and the courts.

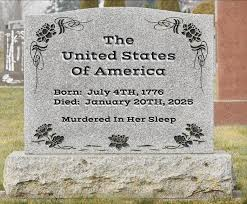

POST MORTEM

We live in a time that demands extraordinary courage and vision. The Trump administration has caused a constitutional crisis that cannot be solved under the current constitution. The sooner we recognize that; the sooner we can create a republic more sustainable for our future. Our old republic has died.

Time of Death: July 1, 2024, with the declaration that presidents have absolute immunity.

Cause of Death: the cancer of pervasive plutocratic influence, spreading throughout civil society—including all levels of government, foreign policy, military, police, finance, media, religion, education, science, technology, and the arts.

In an effort to continue to hide Trump’s sedition on January 6 as well as his criminal mishandling of classified documents, Republicans refused to allow a live public hearing of Jack Smith’s testimony on these matters. Instead, they released the 8 hours of testimony in the waning hours of 2025. Here’s the link to the full hearing. https://youtu.be/6YR8slAt3Ek?si=5JB4ryjEZx8YrdWO