The Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal today of a case involved prosecution under an Illinois law that made it felonious eavesdropping to audio record police acting in public without first gaining their permission. The law was used to punish those who tried to monitor police actions.

In that critical lower-court ruling in May, the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals found that the law — one of the toughest of its kind in the country — violates the First Amendment when used against those who record police officers doing their jobs in public.

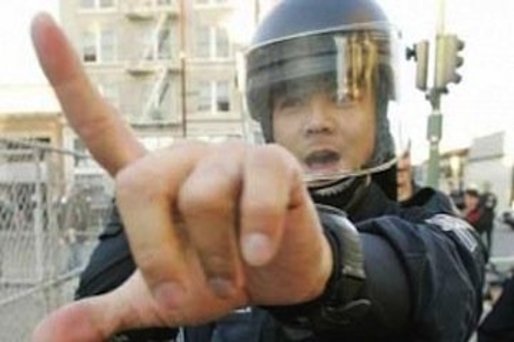

Civil libertarians say the ability to record helps guard against police abuse. The law’s proponents, however, say it protects the privacy rights of officers and civilians, as well as ensures that those wielding recording devices don’t interfere with urgent police work.

The Illinois Eavesdropping Act, enacted in 1961, makes it a felony for someone to produce an audio recording of a conversation unless all the parties involved agree. It sets a maximum punishment of 15 years in prison if a law enforcement officer is recorded.

…

[The case] stems from a 2010 lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union seeking to block Alvarez from prosecuting ACLU staff for recording police officers performing duties in public — one of the group’s long-standing monitoring missions.

The District Attorney for the Chicago area argued in a brief that discarding the law would make citizens less willing to talk to the police in public for fear of being monitored by long-distance surveillance devices.

Does this mean that it’s as safe to do this in Orange County as it will now be in Chicago? Not necessarily — although without the harsh sort of Illinois law on the books anywhere here, we won’t really know. By not taking the appeal, the Supreme Court simply allows the lower-court ruling to cover the Midwestern states within the Seventh Circuit. Often the court will only take a case where there is a split between two or more circuits on a point of law.

The larger problem for those who would record police actions is that while recording the police is not illegal as a rule, according to this decision, it can still be illegal in practice in a given instance if it interferes with official police business. Police have made that argument against protesters in the past — and it’s unlikely that a court would bar that justification for arrest entirely. Whether someone interfered by recording police activity would have to be determined on a case-by-case basis — which can, of course, be expensive and upsetting for the accused. Still, while this decision doesn’t apply to California, the likelihood that a court will find that one can legally record the police in public without their permission in our state has just increased. For those who think that a monitored police force is a better police force, that’s a significant victory.

I am ADD and bipolar and accorfing to the Americans with dissbilitied act i cam tape and record FTDS

In my case I will continue to record police activites, but I am aware that they can take away my camera and either return it broken or erased. There is a similar law being tossed around in Spain to cover up police brutality. http://rt.com/news/spain-ban-photos-police-794/

I think governments around the world are getting anxious about their citizens no longer putting up with their abuses and will try anything to reinstate “fear” to control the masses. But you can’t un-ring a bell!

They can’t take it legally without a warrant and they can’t erase it without compensating you for the loss.

I was able to reduce my “per-day-frequency-of-harassment” by Orange County law enforcement by about 80-90% simply by overtly videotaping them. The concept of it’s illegality will reside in the trash heap of history one day.

If you talk to some of the cops in your city, they will tell you that within 5 years every cop will be wearing cameras and video full time. It’s best for everyone. Cops and non cops. Just a matter of money right now but cops want it big time. Ask one next time you get the chance.

That sounds like a great idea especially if the video is streamed back real time so it can’t be erased.

No the cops don’t want it. Ask Albert Rincon.