Yesterday, our Anaheim districts lawsuit marathon kicked off with a post introducing concepts and context you’ll want to know to understand the importance of, and the weaknesses of, the Demographer’s Report. Of course, if you haven’t read it, you’ll want to go do so immediately. Not interested yet? OK, here’s a quick recap. I briefly review how Anaheim got to the position it was in last Tuesday night, which was described in previous articles here (from before the meeting) and here (mine after) and here (Cynthia Ward’s, I think both during and after).

You’ll want to bone up on terms like “Murrjority” and “the Demographer’s Report” (capital-D, capital R) in the introduction. But the main thing you’ll want to refer to is section 2, which is a glossary of terms that will help you, regardless of your background, evaluate social scientific research. This is, by the way, what the court will do. References to concepts explained back in the previous story will be color-coded here for your convenience, including the concepts of operationalization, outliers, and two entries on sample bias. We begin with section 3.

3. A Slide-by-Slide Recap (skewed, but only because of where I was sitting) of the Demographer’s Report

Note: I took photos of every slide of the Demographer’s Report except some of the titles. So you’ll be able to “enjoy” it, as well as my color commentary, without watching the video. (I know that this heavy use of slides is going to make this story hell to print off, so I suggest that you just cut and paste the text if you want a copy.) Sadly, I began by taking photos of the monitor screen right in front of me; when I reviewed them and saw that they were hard (although not impossible) to read, I instead took shots (from a slightly crazy angle) of the slide screen itself.

Slide 1, Key Take-Away Points: This may seem strange, but I’m starting with this slide from the very end. At the end of the story, I’ll return to this slide.

These are the main ideas that the Demographer wants the Council and the audience — and, I presume, more importantly, Judge Franz Miller — to understand from his report. Presented for now without comment, these are: (1) that if Anaheim Latinos lack political clout in elections now, their clout will naturally increase over time; (2) that while many Latinos are under 18 now, they will get older and become part of the city’s electorate, and (3) we can judge how well Latinos should be expected to do politically in Anaheim’s future by how well they have done in the past.

As I promised: no comment, yet. Well, almost no comment: each suggests that it the courts would just leave alone the problem of inadequate Latino political power in Anaheim, it will take care of itself soon enough.

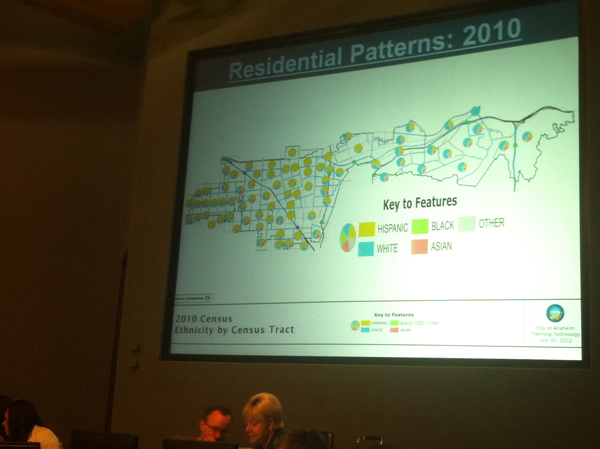

Slide 2, Anaheim’s Residential Patterns: This is a very useful slide. (And those people who want the Census to stop collecting data on race and ethnicity, please understand that you would thus make this sort of analysis impossible.) Here you see dozens of pie charts, one for each precinct in the city. In each chart, the share of non-Hispanic whites (I’ll abbreviate that as “non-H whites) is depicted in blue, the share of Latinos is in yellow, the share of Asians is in orange, and so on. If this tends to confirm your intuition that Latinos tend to live west of the 55, you’re right! But there’s more to the story than that.

The point of establishing voting districts in the city is to allow voters more control over at least one seat on the City Council. Specifically, the point is to give Latinos, who have generally seen their preferred candidates win only when Anaheim Hills or the Resort District interests also support them, more self-representation. (Admittedly, it’s true that Disney thralls Eastman and Brandman and Kring don’t live in the Hills while resistance Tait and former Councilwoman Lorri Galloway do. There are exceptions. However, my understanding is that Tait and Galloway were initially elected with the backing of the Resort District interests.)

The power of the Resort District, without much population but with lots of commercial interests, is of course technically in the flatlands. That’s one reason why any claim on the part of politicians that they are doing all sorts of wonderful things “for the flatlands” have to be probed to determine what they actually mean. They could be truly helping the poorer communities — or, they could be talking about helping the Resort District, which is in the flatlands but more of the Hills. The Gardenwalk Giveaway, the ARTIC station, the proposed Disney-but-not-Disney streetcar, the publicly funded parking structure at Disneyland, and many more can, after all, be described as “subsidies to the flatlands.” That’s just misleading.

Assuring political power for the flatland communities means not only drawing district lines, but drawing fair district lines rather than gerrymandered ones. We know generally how one major split will occur — Anaheim Hills vs. Other — but the devil in in the details. Lines have to avoid both “vote packing” (stuffing too many Latinos into a small number of districts so as to limit their influence) and “vote dilution” (dividing up communities to prevent them from getting a majority in as many districts as they may wish.

While Dr. Morrison presented slides, shown below, showing how it’s hard to draw districts that ensure that Latinos get their choices, the assumptions behind those slides will be shown to be inapplicable. In fact, I have video of Dr. Morrison saying so. (I don’t often do video interviews for this blog, but when I do I try to make them good ones.) Those appear at the bottom of Saturday’s story.

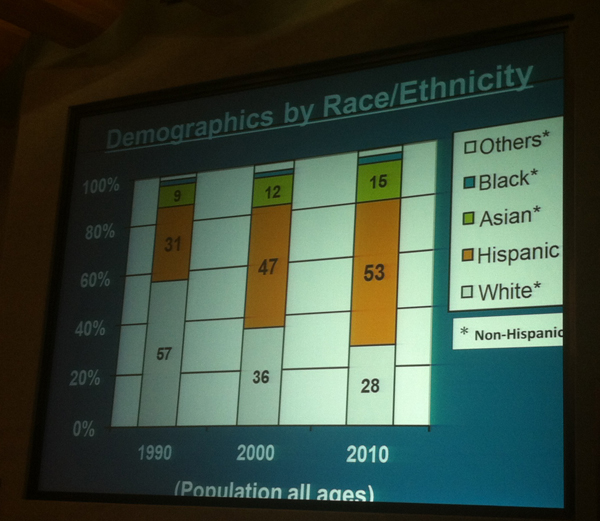

Slide 3, Anaheim’s Changing Demographics: Now we get into analysis of how the race and ethnicity of Anaheim’s population is changing. As you can see, Anaheim’s population is getting less non-H white and more Latino and Asian. (Note that the colors assigned to each have changed since the previous slide.) I presume that I haven’t lost anyone yet.

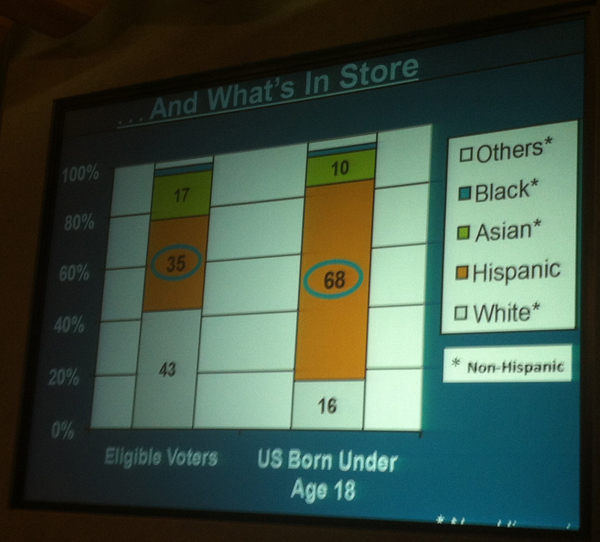

Slide 4, Change in Distribution of Eligible Voters: However, the pool of eligible voters is not the same as the pool of residents. Some of you may jump to the conclusion that this is mostly a matter of the Latino areas of Anaheim being full of people who are in the country without official authorization (either illegally or undocumented, depending on your taste.) Not so much. For example, many Anaheim residents are here with authorization, but are unable to vote — as with green card holders (non-citizen permanent residents) or people here on visas. (Also, people who are in jail for felonies may not vote.)

The much more common category explaining this discrepancy, though, is … people under 18. The Anaheim Hills are composed of a high number of adults, without so many kids. (Note: I did not just say that there are no children living in Anaheim Hills. Read the previous sentence again if you need to.) People in the flatlands have a lot of kids. They still get political representation — yes, that question had to go all the way to the Supreme Court, but it’s now settled — but they themselves don’t get to vote. (That’s one reason why the influence of Anaheim Hills is so outsized.) And, when I say that those under 18 (and green-card holders, etc.) still get political representation, I mean that they still get political representation if there are districts. If you don’t have districts — that is, if you don’t draw lines — then the question of how much political representation they have doesn’t even arise.

And that is the essential reason that the Murrjority does not want to draw “real voting district” lines. Once you do that, you have to give those districts power proportional to the number of people — not voters, but people overall — that they represent. The districts in the flatlands would have fewer voters per resident. Their votes can be swamped by Anaheim Hills in an at-large election — but as soon as voting districts are introduced, they can’t.

Most of what Kris Murray had to say last Tuesday was designed obfuscate this basic fact.

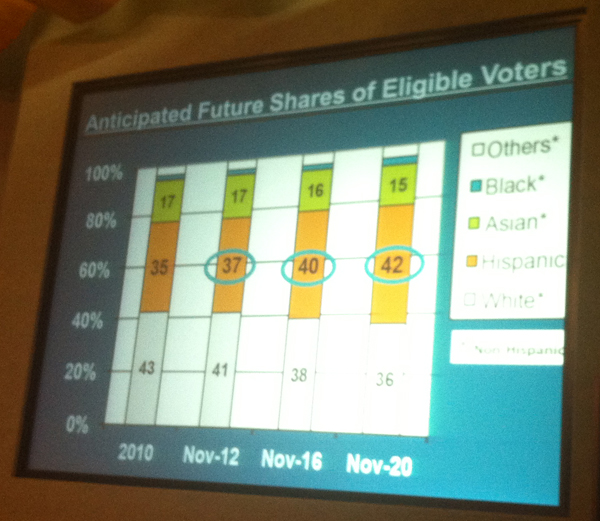

Slide 5, Future Change in Distribution of Eligible Voters: Don’t take it from me, take it from Dr. Morrison! However, he said something that elicted my first moment of puzzlement in his presentation. He said that this showed that Anaheim’s future electorate would be substantially different. That is very likely correct, but — well, it proves nothing of the sort. Drawing a direct extrapolation from this data — which I’m confident he’d deny doing if questioned, requires two unsupported assumptions: (1) that those currently underage Latinos will stick around and (2) that adult non-Latinos won’t stream into the area. If Anaheim experienced “gentrification” — raising property values and expelling residents of lesser means, perhaps involving the bulldozing of existing homes and their replacement with — oh, I don’t know, gated communities — than this isn’t going to happen. The importance of that is that a court can’t rely on it happening. Murray’s presentation includes the argument that based on demographic changes “the problem will solve itself.” That’s wrong for more than one reason — look, at the example of neighboring Stanton, which is largely Latino, has majority Democratic voter registration, and has completely non-Latino and Republican City Council — but its being speculative is enough to undermine the argument.

Slide 6, Anticipated Distribution of Future Eligible Voters: So, in other words, one can do calculations like this, but they’re not really compelling. They depend on unsupported assumptions, as outlined above. (If you’re wondering why, eight months after the 2012 election, we still have an estimate for the “Nov-12” column — well, so do I.)

Now, are the unsupported assumptions behind this slide a big problem? Not really, at least relatively. If the problems with unsupported assumptions that I raise later are boulders, this one is just a small smooth stone. The problem is that the numbers on the right of the chart look just like the numbers on the left side, that were actually obtained. In fact, each of those numbers in the right three bars should be a range, with a big asterisk or two noting the assumptions, rather than invite the reader to infer precision into what is actually a big estimate.

Slide 7, John Leos Finished Third in 2012! Get it?: Here, I want to direct you to the discussion in Saturday’s glossary (section 2, remember?) of “operationalization.” (This, by the way, is where I think that a look of horror first came over my face as I sat two rows behind Dr. Morrison. “He’s not really going to do that, right?”, I thought to myself. But he did.)

What is the significance of a Latino candidate named John Leos getting 14% of the vote (and a third-place finish) in 2012? This will be assigned three major points of significance:

- “Look, see, Leos finished third, so Latinos have a lot of influence!”

- “If only we had three seats up in the 2012 election rather than two, Leos would have won.”

- “This proves that Latinos do have political power in Anaheim!”

These are really important points to understand — and they’re all flat wrong.

1. Leos finished third because Anaheim’s business interests only fielded two strong candidates, as is appropriate for two open seats.

How many serious candidates does a political faction (such as the business interests of the Resort District and the Building Trades allied with them — or, alternatively, “Latinos”) want to put on the ballot if there are two seats up for election?

Two. Exactly two.

If the faction offers only one candidate, it guarantees that it will hold only one seat. That’s obvious. Less obvious but no less important, if a faction offers three or more candidates for two seats, it will split the vote among them. Between them, Brandman and Kring got about 52,000 votes. Now if we add in a third candidate who is equally strong as the two of them but pulls from the same pool of potential voters, each of them and that third candidate get 17,000 votes apiece — and Leos wins.

(I know what some of you are thinking: “What about Steven Albert Chavez Lodge?” Wasn’t he the “third candidate” in the above model? In a way, he was — and in a way, he wasn’t. “Steve Lodge” would have been that “third candidate” and taken more of the vote from others who were twice as strong as him. Steven Albert Chavez Lodge, though — and remember that he hadn’t used the name “Chavez” since childhood — was present on the ballot in part to split the Latino vote. If he had done well enough to defeat the somewhat unpredictable and highly unreliable Lucille Kring, the business interests probably would have been even happier — but he didn’t have to win for them to achieve their objective of keeping Leos off of the Council. His function in the election was (1) to split the Latino vote and (2) to boost his buddy Brandman by allowing him to campaign next to a Spanish-surnamed partner in the Latino communities. Of these, the former — taking Latino votes for a “Brandman-Lodge” ticket as opposed to leaving Latino voters to cast a possible “Brandman-Leos” ticket — was the more important.

To understand this, one has to know how the political factions were arrayed in Anaheim — and here I’ll have to paint with a very broad brush. First, understand that the unions in Orange County are not all politically aligned. The public safety unions (police, fire, prison guards) tend to be off in one category, socially conservative but interested in protecting and increasing their numbers and compensation. The building trade unions (carpenters, electricians, plumbers, and in OC usually aligned with the Teamsters etc.) tend to be more involved in broader “labor solidarity” but are also in a de facto alliance with the major building interests that want public money spent on construction and operation. (So you have the “trades” supporting hotel construction, keeping San Onofre open, toll lanes on the 405, Poseidon desalination — anything that might bring them more jobs. Sadly, the promise of more jobs doesn’t necessarily turn into a reality, as when building interests accept support from unions to help get a project approved — and then hire non-union workers anyway.) Finally, the public service unions (teachers, government employees, etc.) and the commercial services unions (restaurant workers, hotel workers, etc.) tend to be more liberal and usually less aligned with the people who pay them. Note that this analysis will be different in other counties: in San Diego, for example, I’m told that the building trade unions tend to be quite liberal.

Brandman was the only prominent Democrat in the race — and he’s primarily tied to the building trades. (Why? Maybe he just loves building trade unions — or maybe he’s attracted to the wealthy commercial interests with whom they’re allied.) That’s why he got the Democratic Party endorsement despite lots of grumbling from the non-building trade unions. So his power base among voters — despite his ethnicity — would have been largely Latino Democrats, along with corporate interests who gave him a lot of money to reach them.

Leos was the most prominent Latino — but he was also a Republican, which is not the preferred party of most Anaheim Latinos. He was the favorite of the public service unions such as OCEA, the Orange County Employee’s Association. So you can see that both Leos and Brandman had one mark for them and one mark against them when it came to the Latino community — Latino Republican versus non-H white Democrat. But in terms of their financial support, both came from unions and allied interests: Leos from the public service unions and Brandman from the coalition of building trades and developers/vendors who wanted public money and fewer regulations.

Is it obvious where “Latino interests” lay in such an environment? No? Then you may agree that Leos’s finishing third doesn’t necessarily mean much of anything about Latino influence. (Personally, at first I thought that his name was Greek.) It’s a bad way to operationalize and measure Latino influence. Add in the role that money plays in such a race and it becomes a terrible way. (The performance of Brian Chuchua and Rudy Gaona may indicate what a Latino name will get you without any money; Jennifer Rivera’s shows what you may get in the Latino community without money if you share a name with someone quite famous.)

Beyond this, there’s the factor of splitting the vote (addressed yesterday) — and all in all one is left screaming “what does it really prove than John Leos finished third?” What it doesn’t prove — or even suggest — is that Anaheim is not violating the California Voting Rights Act.

2. The Demographer admits that this would be meaningful only under circumstances that don’t and won’t exist.

Take a look at the transcript of my second interview with Dr. Morrison:

GD: How do you rule out the prospect that if there was one party that was pushing the people in there for two seats, that they would only run two candidates – there’s no reason to run a third candidate because it would split the vote – and that if there were three positions they would have run three candidates? And if there were four then they would have run four?

PM: That’s why I say that it’s a mental experiment, because I have to assume that nothing else changes. Of course, if the structure of the electoral system changes, that creates a whole set of new incentives and maybe then different people will respond in different ways. That’s why I say that all you have to go on is the history, and if you look at the history you say that this is all we can [account for?] –

GD: So there was a conclusion from the dais for example that, if we had done it this way with six seats, then John Leos would have been elected, but in fact we don’t know that to be true!

PM: That would be true if nothing else changed.

GD: But if a third candidate had run that was similar to Kring and to Brandman, that it may well be that theywould have won!

PM: Yeah, but that’s purely hypothetical. You can imagine anything….

The first part of this conversation addresses the “a faction runs only two candidates” notion. Then, Dr. Morrison admits that he “has to assume that nothing else changes.” But of course something else would change if the structure of the electoral system changed. Specifically, the business interests that have literally gotten over a half a billion dollars out of the Council in the past year or so would have given ample funding to yet a third candidate — maybe Steve Lodge, maybe one of the appointees to one of the Commissions, but someone who was not John Leos or Brian Chuchua — so that they could control as many seats on the Council as possible.

Yeah, that’s “hypothetical” — but it’s a lot more likely than the notion that “nothing else [would have] changed” — that the “Masters of the Universe” would just say “oh, darn, there are three seats open, I guess we have to resign ourselves to the possibility that Leos is going to win. Maybe you have to go beyond Demography into something like Political Science to be able to see it, though. My guess is that if you run that election again with three Council seats open, Leos finishes fourth, because his opponents were prepared to spend what they had to spend to do to make that happen. And if you make it four Council seats open, he finishes fifth.

Slide 8, But John Leos Finished Third Twice! TWICE!!: This is why the next slide shown, reminding us that John Leos also finished third in 2010, is about as cruel of a joke as a carnival game worker telling a customer that “ohh, you were sooooo close to knocking over that milk bottle.” The carnival worker doesn’t care how close you got. He knows that the game is fixed against you. He wants you to read into your coming so close that you might have won and should keep playing as if you have a fair chance. But — you don’t. When the city’s business interests can run as many people (as a de facto “slate”) for seats as there are openings, expecting to win one’s initial race is a sucker’s bet. The Murrjority wants to keep it that way.

How can one fix this? One way is to let Leos run in a small enough district that the brute force of money makes less of a difference and that the electorate might be more favorable to him (except for that “Republican” bit.) Disney and friends might still be able to pump in enough money to win the election — but doing something like hiring a thousand attractive young Latino and Latina canvassers to knock on every door twice each week might attract a little more attention than they’d prefer.

3. One seat isn’t a majority

Here’s in some ways the most basic problem with the idea that Leos’s finishing third is particularly meaningful: if he had won one race, SO WHAT? The issue at hand — yeah, this is “operationalization” of the concept of “adequate political representation — isn’t “can Latinos elect someone to City Council?” but something more like “can Latinos obtain representation on City Council proportional to their power within the population — correcting, of course, for factors such as campaign resources, political expertise, and amount of effort. That Latinos could wangle a third-place finish each year — giving them two whole seats on a seven person Council! — would not give them political representation proportional to their power within the population. (Under such circumstances, they couldn’t even block a motion that required a 2/3 majority; they couldn’t even win a simple majority vote even with a sympathetic Mayor.)

Every single argument you hear that derives from the argument that “look, John Leos already finished third!” is pointless. And, as we’ll note tomorrow, one argument that Kris Murray made from the dais did, sure enough, derive from the argument that things must not be that bad for Latinos … because John Leos finished third in 2012.

NOTE: I’m ending this one here, as it’s already more than long enough. I’ll get to the rest of the slides — with, I expect, less commentary — later today.

”Why operationalize as Latino voting power as ‘election of Latino candidates’ rather than ‘Latinos being able to get their favored candidates onto Council’?” resumes well the weakness of Mr Morrison’s report.

However, your statistical analysis alone does not comprehensively support that “Leos finished third because Anaheim’s business interests only fielded two strong candidates, as in appropriate for two open seats”

The unpredictable and highly unreliable Lucille Kring did not seem to be one of their strong candidates.This explains the high financial debt of her campaign. Leos did not fare better due to the power of the Baugh manifesto. Relevant single issues like crime and gang explain the significant percentage of votes of the two former cops, Lodge and Linder. The business interests only needed Brandman.

You know how I enjoy a good argument, Ricardo — actually, I usually enjoy a bad one too — but whether or not the 2012 Anaheim City Council campaign fit the template (as for example the 2010 election clearly did), the basic point still holds true.

Still, I’ll argue just a little: I think that the size of Kring’s victory shows that the business interests had decided to support her. And while they may have only needed Brandman to get three votes, a fourth vote allows them to keep the heat off Brandman — heat that would be there if he casts a significant deciding vote in their favor. As I think I’ve mentioned before, if Kring ever wants to mess with Brandman she’ll change her vote on one of the issues where he and Tait are in the minority — and watch him struggle with whether the change his as well. (My guess is that he wouldn’t — he’d just move to reconsider at the next meeting.)

Actually the business interests fielded Brandman and Chavez-Lodge, not Kring. Kring won on the strength of her tireless campaigning, her name recognition, and the OC GOP endorsement. Of course NOW she does whatever the business interests tell her too, because they’re paying off all her old campaign debts, so they did end up getting what they wanted.

Leos failed partly because SO much money was spent attacking him, in very clever ways: Republicans all got mailers calling him a UNION TOOL, and Democrats (and latinos) all got mailers calling him a SCARY TEA-PARTYING REPUBLICAN.

At first they favored Chavez-Lodge — until Cynthia messed him up. At the end, they went hard after Leos, knowing that Lodge wasn’t likely to win. They could have gone after Kring as well — but they didn’t. That left them as de facto supporters of Kring — who evidently got a lot of money donated from some quarters after the election.

(Again, this is all ancillary to the main point of the post. I admit that it wasn’t as clear as Murray/Eastman in 2010.)

They attacked Kring too, I posted one of their Kring attack flyers. But not as relentlessly. And yes, this is ancillary. Are we gonna race tomorrow to see who finds out what happens first?

I have really wanted to attend the hearing, but I think that “real work” is going to keep me from it. Anyone there — contact me with reports if you have my info! (Or we can deputize you as a writer!)

I would be there, but it’s just gonna be lawyers in judge’s chambers. We are not invited. But I got the inner track to the ACLU, and I should be able to let OJ readers know before anyone else … probably around noon!

Great. Can you get Anaheim to post their video of the July 2 meeting, too? Going through the audio only, without being able to see who’s talking (so one knows what to skip) is boring and a time-suck.

I agree. It wasn’t as clear as 2010 but it had the same effect. Kring played a mini-Pringle act, making promises but at the end of the day she showed her true colors. Leos also fell victim to the infamous Baugh manifesto. This is another subordinate aspect of the last election, GOP working people rejected by their own party because of the union support. It seems that the manifesto is no longer applied, as Baugh is in the company of the APD Union President supporting Murray.

Hopefully all these subordinate aspects of political hegemony will change after tomorrow.

One thing they teach in Government 101 is that you cannot take a set of factors and apply them to a similar but not identical situation.

In this analysis, Leos 3rd, J. Rivera 4th, etc has zero bearing. A race with 3 open seats would have attracted a completely different set of candidates, different distribution of campaign resources, Attempting to apply these outcomes to a situation not yet encountered is random and strange.

It’s random, strange — and the foundation upon which Anaheim has chosen to build its defense.

It’s 10 a.m. — maybe they regret it by now.